لیــو جیــاکـون

ترجمه این متن توسط محمدرضا خلیلی دانشجوی کارشناسی ارشد معماری صورت گرفته است.

(فارسی)

زنـدگـی نـامـه

مسیر لیو جیاکون به سوی معماری نه خطی بود و نه قابل پیشبینی.

او که در سال ۱۹۵۶ در شهر چنگدو، جمهوری خلق چین، متولد شد، بخش زیادی از دوران کودکی خود را در راهروهای بیمارستان دوم مردم چنگدو ـ که در سال ۱۸۹۲ با نام «بیمارستان گاسپل» تأسیس شده بود ـ گذراند؛ جایی که مادرش بهعنوان پزشک داخلی مشغول به کار بود. او محیط مؤسسهی پزشکی مسیحی را عامل پرورش روحیهی ذاتی و همیشگیاش در مدارا و تساهل مذهبی میداند. با اینکه تقریباً تمام اعضای خانوادهی نزدیکش پزشک بودند، او علاقهای به هنرهای خلاقانه نشان داد و جهان را از مسیر نقاشی و ادبیات کاوش میکرد؛ این مسیر سرانجام باعث شد معلمی او را با رشتهی معماری بهعنوان یک حرفه آشنا کند.

در هفدهسالگی، لیو بخشی از برنامهی «ژچیینگ» چین بود؛ برنامهای که در آن «جوانان تحصیلکرده» به کار کشاورزی حرفهای در روستاها گماشته میشدند. زندگی در آن زمان برایش بیاهمیت و بیمعنا به نظر میرسید، تا اینکه در سال ۱۹۷۸ پذیرش حضور در مؤسسهی معماری و مهندسی چونگچینگ (که بعدها به دانشگاه چونگچینگ تغییر نام داد) را دریافت کرد .او صادقانه اذعان میکند که بهطور کامل درک نکرده بود معماری یعنی چه، اما مانند یک رویا، ناگهان فهمیدم که زندگیِ خودم مهم است.

لیو در سال ۱۹۸۲ با مدرک کارشناسی مهندسی در رشتهی معماری فارغالتحصیل شد و جزو نخستین نسل از فارغالتحصیلانی بود که مأموریت یافتند در دورهای دگرگونکننده برای کشور، چین را بازسازی کنند. او در ابتدای دوران حرفهای خود در «مؤسسهی طراحی و تحقیقات معماری چنگدو» که تحت مالکیت دولت بود، مشغول به کار شد و بهصورت داوطلبانه پذیرفت که بهطور موقت به «ناگچو» در تبت (۱۹۸۴ تا ۱۹۸۶) مرتفعترین منطقهی جهان منتقل شود؛ زیرا به گفتهی خودش: در آن زمان، به نظر میرسید بزرگترین نقطهی قوت من این بود که از هیچچیز نمیترسیدم و علاوه بر آن، مهارتهای نقاشی و نویسندگی داشتم. در طول آن سالها و چند سال پس از آن، او در طول روز بهعنوان معمار فعالیت میکرد، اما در شب به نویسنده تبدیل میشد و عمیقاً در خلق آثار ادبی غرق بود.

او تا آستانهی ترک حرفهی معماری پیش رفت، تا اینکه در سال ۱۹۹۳ از نمایشگاه انفرادی معماری «تانگ هوا»، همکلاسی سابقش در دانشگاه، در موزهی هنر شانگهای بازدید کرد؛ این تجربهی شور و اشتیاق او برای حرفهاش را دوباره شعلهور ساخت و ذهنیت جدیدی به او داد که خودش نیز میتواند از زیباییشناسیهای اجتماعی تحمیلی فاصله بگیرد . او این درک تحولآفرین را ــ که محیط ساختهشده میتواند بهعنوان وسیلهای برای بیان شخصی عمل کند ، لحظهای میداند که واقعاً حرفه ی معماری او آغاز شد. او بهزودی وارد دوران شکلگیری فکریترین سالهای زندگی خود شد و به بحث و تبادل نظر درباره ی هدف و قدرت معماری با همعصرانش پرداخت؛ از جمله هنرمندان «لوو چونگلی» و «هه دوولینگ» و شاعر ژای یونگمینگ.

من همیشه آرزو دارم مانند آب باشم ــ بهگونهای که بتوانم از میان مکانی عبور کنم بدون اینکه شکل ثابتی از خود به همراه داشته باشم و در محیط محلی و خود سایت نفوذ کنم. با گذشت زمان، این آب بهتدریج سفت میشود و به معماری تبدیل میشود، و شاید حتی به بالاترین شکل خلق معنوی انسان. با این حال، همچنان تمام ویژگیهای آن مکان، چه خوب و چه بد، را حفظ میکند.

او در سال ۱۹۹۹ شرکت «جیاکون آرشیتکتس» را در چنگدو تأسیس کرد و با قاطعیت به قدرت متعالی معماری پایبند ماند، در حالی که درک میکرد معماری محصول جامعه، معنویت، سنت و پیشزمینههای موجود است. بخشی از تقدیرنامه ی هیئت داوران سال ۲۰۲۵ چنین بیان میکند: «هویت به همان اندازه که مربوط به فرد است، مربوط به حس جمعی تعلق به یک مکان نیز هست. لیو جیاکون سنت چینی را بازبینی میکند، بدون آنکه رویکردی نوستالژیک یا مبهم داشته باشد، بلکه بهعنوان سکویی برای نوآوری. او معماری جدیدی خلق میکند که همزمان یک سند تاریخی، بخشی از زیرساخت، یک چشمانداز و یک فضای عمومی شگفتانگیز است.

در طول چهار دهه، لیو همراه با تیم خود بیش از سی پروژه را در سراسر چین اجرا کرده است، پروژههایی که از مؤسسات علمی و فرهنگی تا فضاهای شهری، ساختمانهای تجاری و برنامهریزی شهری را در بر میگیرند، و همچنین برای طراحی اولین «پویلن سرپنتاین پکن» (۲۰۱۸) انتخاب شد.

نوشتن رمان و پرداختن به معماری، دو شکل متمایز از هنر هستند و من بهطور عمدی تلاش نکردم این دو را با هم ترکیب کنم. با این حال، شاید به دلیل پیشزمینهی دوگانهام، ارتباط ذاتیای بین آنها در آثارم وجود دارد مانند کیفیت روایی و جستجوی شعرگونه در طراحیهایم.

آثار مکتوب او شامل «مفهوم ماه روشن» (انتشارات ادبیات و هنر تایمز، ۲۰۱۴) که به بررسی تعارض میان آرمانشهرها و زندگی انسانی میپردازد، «گفتمان روایی و استراتژی کمتکنولوژی» (انتشارات معماری و ساختمان چین، ۱۹۹۷)، «اکنون و اینجا» (انتشارات معماری و ساختمان چین، ۲۰۰۲) و «من در غرب چین ساختم؟» (دفتر تحریریهی تودی، ۲۰۰۹) است.

آثار لیو در نمایشگاههای بینالمللی متعددی به نمایش گذاشته شده است، از جمله: «معماری تجربی توسط معماران جوان چینی» – بیستمین کنگره ی جهانی معماران UIA (۱۹۹۹، پکن، چین)؛ «TU MU: معماری جوان از چین» (۲۰۰۱، برلین، آلمان)؛ «خلق شهری»، بینال شانگهای (۲۰۰۲، شانگهای، چین)؛ نخستین، سومین و هفتمین «بینال دوشهری شهرسازی/معماری» (۲۰۰۵، ۲۰۰۹ و ۲۰۱۷، شنژن، چین)؛ یازدهمین و پانزدهمین نمایشگاه بینالمللی معماری «لا بیاناله ونیز» (۲۰۰۸ و ۲۰۱۶، ونیز، ایتالیا)؛ پنجاه و ششمین نمایشگاه بینالمللی هنر «لا بیاناله ونیز» (۲۰۱۵، ونیز، ایتالیا)؛ «اکنون و اینجا – چنگدو | لیو جیاکون: آثار منتخب» (۲۰۱۷، برلین، آلمان)؛ و «ادغام برتر – بینال چنگدو» (۲۰۲۱، چنگدو، چین).

در حال حاضر، او استاد مدعو در دانشکدهی معماری آکادمی مرکزی هنرهای زیبا (پکن، چین) است، و پیشتر در Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine (پاریس، فرانسه) سخنرانی کرده است، همچنین در مؤسسه ی فناوری ماساچوست (کمبریج، ماساچوست، ایالات متحده ی آمریکا) تدریس داشته است، و نیز در آکادمی سلطنتی هنرها (لندن، بریتانیا) و مؤسسات پیشرو در چین سخنرانی کرده است. جوایز او شامل جایزه ی طراحی معماری شرق دور، جایزه ی برجسته (۲۰۰۷ و ۲۰۱۷)؛ جایزه ی بزرگ خلق معماری ASC (۲۰۰۹)؛ جوایز Architectural Record چین (۲۰۱۰)؛ جوایز WA برای معماری چینی (۲۰۱۶)؛ جایزه ی معماری «ساختن با طبیعت»، Architecture China (۲۰۲۰)؛ جوایز Sanlian Lifeweek «شهر برای انسانیت» برای مشارکت عمومی (۲۰۲۰)؛ و جوایز یونسکو آسیایپاسفیک برای حفاظت از میراث فرهنگی، طراحی جدید در زمینههای میراث (۲۰۲۱) بوده است.

لیو همچنان به فعالیت حرفهای خود ادامه میدهد و در چنگدو، چین زندگی میکند، و از طریق آثار خود، زندگی روزمرهی هموطنانش را در اولویت قرار میدهد.

در حال حاضر، او استاد مدعو در دانشکدهی معماری آکادمی مرکزی هنرهای زیبا (پکن، چین) است، و پیشتر در Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine (پاریس، فرانسه) سخنرانی کرده است، همچنین در مؤسسه ی فناوری ماساچوست (کمبریج، ماساچوست، ایالات متحده ی آمریکا) تدریس داشته است، و نیز در آکادمی سلطنتی هنرها (لندن، بریتانیا) و مؤسسات پیشرو در چین سخنرانی کرده است. جوایز او شامل جایزه ی طراحی معماری شرق دور، جایزه ی برجسته (۲۰۰۷ و ۲۰۱۷)؛ جایزه ی بزرگ خلق معماری ASC (۲۰۰۹)؛ جوایز Architectural Record چین (۲۰۱۰)؛ جوایز WA برای معماری چینی (۲۰۱۶)؛ جایزه ی معماری «ساختن با طبیعت»، Architecture China (۲۰۲۰)؛ جوایز Sanlian Lifeweek «شهر برای انسانیت» برای مشارکت عمومی (۲۰۲۰)؛ و جوایز یونسکو آسیایپاسفیک برای حفاظت از میراث فرهنگی، طراحی جدید در زمینههای میراث (۲۰۲۱) بوده است. لیو همچنان به فعالیت حرفهای خود ادامه میدهد و در چنگدو، چین زندگی میکند، و از طریق آثار خود، زندگی روزمرهی هموطنانش را در اولویت قرار میدهد.

اطلاعیه(مبانی نظری لیو جیاکون)

شیکاگو، ایلینوی (۴ مارس ۲۰۲۵) – جایزهی معماری پریتزکر اعلام کرد که لیو جیاکون، از چنگدو، جمهوری خلق چین، بهعنوان برندهی جایزهی معماری پریتزکر ۲۰۲۵ انتخاب شده است؛ جایزهای که بهطور بینالمللی بهعنوان بالاترین افتخار در معماری شناخته میشود.

لیو بیان میکند: «معماری باید چیزی را آشکار کند باید انتزاعی کند، تقطیر کند و ویژگیهای ذاتی مردم محلی را قابل رؤیت سازد. معماری توانایی شکل دادن به رفتار انسانی و خلق فضاها را دارد، حس آرامش و شعرگونهای ارائه میدهد، ترحم و مهربانی را برمیانگیزد و حس جامعهی مشترک را پرورش میدهد.»

لیو با درهمآمیختن دو قطب بهظاهر متضاد مانند آرمانشهر در برابر زندگی روزمره، تاریخ در برابر مدرنیته و جمعگرایی در برابر فردیت، معماریای ارائه میدهد که زندگی شهروندان عادی را تأیید و جشن میگیرد. او قدرت متعالی محیط ساختهشده را از طریق همآهنگی ابعاد فرهنگی، تاریخی، عاطفی و اجتماعی حفظ میکند و از معماری برای شکل دادن به جامعه، الهامبخشی به همدلی و ارتقای روح انسانی بهره میبرد.

لیو جیاکون از طریق مجموعهای برجسته از آثار با انسجام عمیق و کیفیت مداوم، جهانهای جدیدی را تصور و خلق میکند که از هرگونه محدودیت زیباییشناختی یا سبکی آزاد است. به جای پیروی از یک سبک، او راهبردی توسعه داده است که هرگز بر روش تکراری تکیه نمیکند، بلکه بر ارزیابی ویژگیها و نیازهای خاص هر پروژه بهطور متفاوت تمرکز دارد. به عبارت دیگر، لیو جیاکون واقعیتهای کنونی را در نظر میگیرد و آنها را تا جایی مدیریت میکند که گاهی یک سناریوی کاملاً جدید از زندگی روزمره ارائه میدهد. فراتر از دانش و تکنیکها، عقل سلیم و خرد، قدرتمندترین ابزارهایی هستند که او به جعبهابزار طراح اضافه میکند»، بخشی از بیانیهی هیئت داوران ۲۰۲۵ بیان میکند.

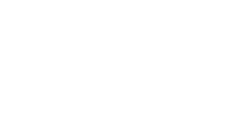

لیو فضاهای عمومی در شهرهای پرجمعیت ایجاد میکند، جایی که تجمل فضا عمدتاً غایب است، و رابطهای مثبت بین تراکم و فضای باز شکل میدهد. با چند برابر کردن تیپولوژیها در یک پروژه، او نقش فضاهای مدنی را نوآورانه میکند تا گستره نیازهای یک جامعه متنوع را پشتیبانی کند. «وست ویلج» (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۱۵) پروژهای پنج طبقه است که یک بلوک کامل را در بر میگیرد و از نظر بصری و زمینهای با ماتریس ساختمانهای معمولاً میانبلند و بلند تضاد دارد. یک محیط باز اما محصور با مسیرهای شیبدار برای دوچرخهسواران و عابران پیاده، شهر زندهای از فعالیتهای فرهنگی، ورزشی، تفریحی، اداری و تجاری را درون خود احاطه میکند، در حالی که به عموم امکان میدهد تا از درون آن، محیطهای طبیعی و ساختهشده اطراف را مشاهده کنند. دانشکده مجسمهسازی مؤسسه هنرهای زیبا سیچوان (چونگکینگ، چین، ۲۰۰۴) راهحل جایگزینی برای بیشینهسازی فضا ارائه میدهد، بهطوری که طبقات بالایی به بیرون پیشآمده و متراژ یک پایه باریک را افزایش میدهند.

آلخاندرو آراوِنا، رئیس هیئت داوران و برنده جایزه پریتزکر ۲۰۱۶ اظهار میکند. «شهرها معمولاً تمایل دارند عملکردها را جدا کنند، اما لیو جیاکون رویکردی مخالف اتخاذ میکند و تعادلی ظریف برای یکپارچهسازی تمام ابعاد زندگی شهری حفظ میکند»،او ادامه میدهد: «در جهانی که تمایل دارد پیرامونهای بیپایان و یکنواخت ایجاد کند، او راهی یافته است تا فضاهایی بسازد که همزمان ساختمان، زیرساخت، چشمانداز و فضای عمومی باشند. آثار او ممکن است سرنخهای تاثیرگذاری در مواجهه با چالشهای شهری در عصری که شهرها به سرعت در حال رشد هستند، ارائه دهد.»

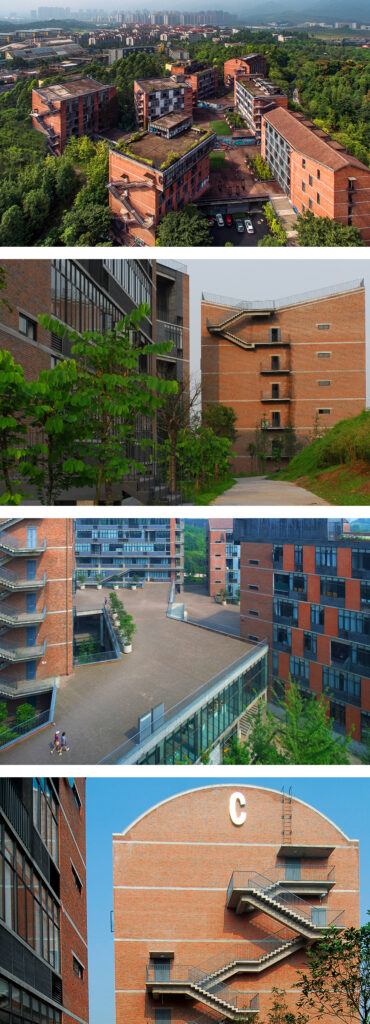

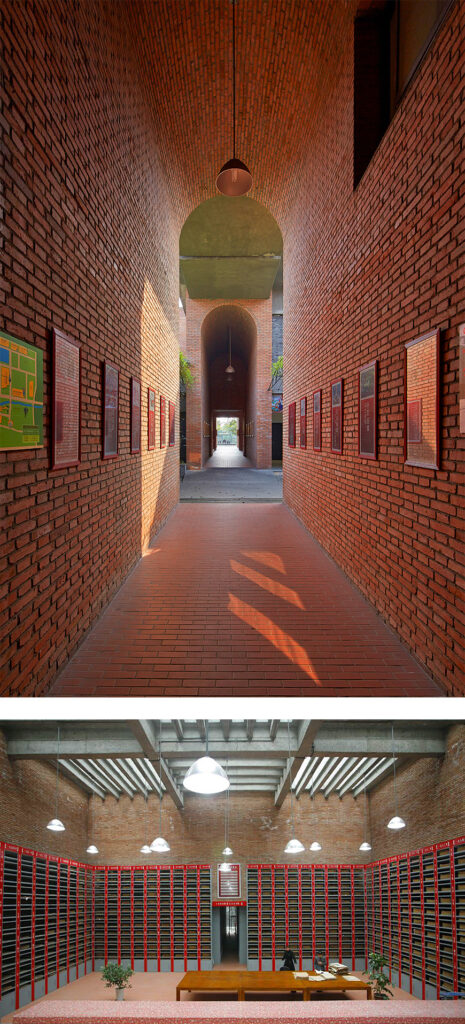

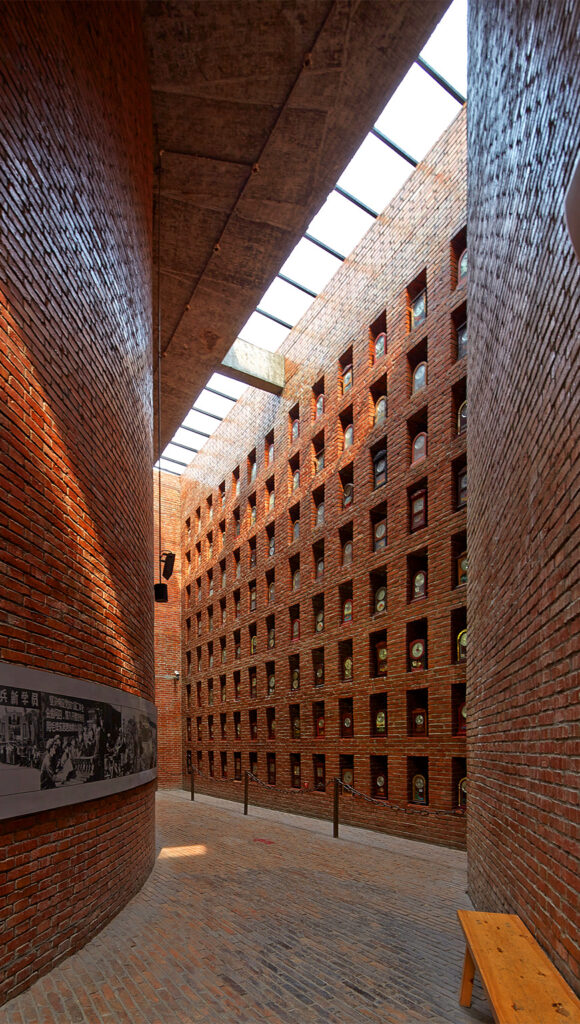

در سراسر آثار خود، لیو احترام خود را نسبت به فرهنگ، تاریخ و طبیعت نشان میدهد و با روایت زمان و ایجاد حس آشنایی برای کاربران از طریق تفسیرهای مدرن معماری کلاسیک چین، آنها را آرامش میبخشد. ایوانهای صاف موزه آجر کوره امپراتوری سوجو (سوجو، چین، ۲۰۱۶) و دیوارهای پنجرهای تالار لانچوی خلیج اگرت (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۱۳) شکل ایوانهایی را بازآفرینی میکنند که به هزاران سال پیش بازمیگردند. بالکنهای چندطبقه پروژه نوارتیس (شانگهای) – C6 (شانگهای، چین، ۲۰۱۴) یادآور برجهایی هستند که نمایانگر سلسلههای متعدد بودهاند. موزه هنر مجسمهسازی سنگ لویییوان (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۰۲)، که میزبان مجسمهها و آثار بودایی است، بر اساس باغ سنتی چینی طراحی شده و آب و سنگهای باستانی را متعادل میکند تا چشمانداز طبیعی را منعکس نماید. باور دارد که رابطه انسان با طبیعت دوطرفه است، ساختمانها هم در محیط اطراف خود پدید میآیند و هم در آن حل میشوند، مانند بازسازی منطقه غار تیانباو در شهر ارلانگ (لوزو، چین، ۲۰۲۱) که در مناظر سرسبز صخرهای کوه تیانباو جای گرفته است. در تمام آثار او، گیاهان محلی و خودرو مورد توجه قرار گرفتهاند؛ آجرها بهصورت عمودی چیده میشوند تا چمنها بتوانند از سوراخهای مرکزی رشد کنند، درختان بامبو بومی در سایتهای جدید کاشته میشوند و کفها و سقفها با بازشوهایی طراحی شدهاند تا ادامه رشد درختان موجود ممکن شود.

معماری صادقانه او، صداقت مصالح و فرآیندهای متریالی را نشان میدهد و نقصهایی را به نمایش میگذارد که با گذر زمان از بین نمیروند، بلکه دوام مییابند. او محصولات صنعتی را نمیپسندد و به صنایعدستی سنتی گرایش دارد و اغلب از مصالح خام محلی استفاده میکند که اقتصاد و محیطزیست را پایدار نگه میدارند و برای جامعه و توسط جامعه ساخته شدهاند. ساختمان دپارتمان مجسمهسازی، جزئیات مارپیچی و واقعی کار گچکاری سنتی چونگکینگ را نشان میدهد که به جای صیقل دادن، بهصورت آشکار باقی ماندهاند. او مصالح و روحها را احیا میکند؛ با استفاده از آوار باقیمانده از زلزله وِنچوان ۲۰۰۸ و تقویت آن با الیاف گندم محلی و سیمان، آجرهای مستحکمی تولید میکند که از نظر فیزیکی و اقتصادی کارآمدتر از نمونه اصلی هستند. این «آجرهای تولد دوباره» بهطور گسترده در ساختمان نووارتیس، موزه شویجینگفانگ (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۱۳) و وست ویلج، بزرگترین اثر او، بهکار رفتهاند. ویرانی همچنین کوچکترین اثر او تا به امروز، یادبود هو هویشان (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۰۹)، را بهوجود آورد؛ اثری به شکل یک رلیف دائمی سیمانی شبیه چادر، که نه تنها برای دختری ۱۵ ساله پس از تخریب ساخته شد، بلکه برای حافظه جمعی یک ملت در سوگواری نیز به نمایش درآمد.

تام پریتزکر، رئیس بنیاد هایت که اسپانسر جایزه است، اظهار میدارد: «لیو جیاکون از طریق فرایند و هدف معماری انسانها را تعالی میبخشد و ارتباطات احساسیای ایجاد میکند که جوامع را متحد میسازد. در معماری او خردی نهفته است که فراتر از سطح میاندیشد و نشان میدهد تاریخ، مصالح و طبیعت با یکدیگر همزیستی دارند.»

فعالیت حرفهای لیو بیش از چهار دهه گسترده است و شامل بیش از سی پروژه میشود که از مؤسسات آموزشی و فرهنگی گرفته تا فضاهای شهری، ساختمانهای تجاری و برنامهریزی شهری در سراسر چین را در بر میگیرد. آثار مهم او همچنین شامل موزه ساعتها در مجموعه موزه جیانچوان (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۰۷)، دپارتمان طراحی در پردیس جدید مؤسسه هنرهای زیبا سیچوان (چونگکینگ، چین، ۲۰۰۶)، مرکز اقامتی نمایشگاه بینالمللی عملی معماری چین (نانجینگ، چین، ۲۰۱۲)، مرکز ارتباطات پارک نرمافزار تیانفو منطقه فناوری پیشرفته چنگدو (چنگدو، چین، ۲۰۱۰) و محله فرهنگی سونگیانگ (لیشویی، چین، ۲۰۲۰) میشود.

لیو پنجاه و چهارمین برنده جایزه معماری پریتزکر و بنیانگذار شرکت معماری جیآکون است که در سال ۱۹۹۹ تأسیس شد. او در چنگدو، چین متولد شده و در شهر زادگاهش زندگی و فعالیت میکند. او در بهار امسال در ابوظبی، امارات متحده عربی مورد تجلیل قرار خواهد گرفت و بهصورت جهانی نیز با یک مراسم ویدیویی مجازی در پاییز معرفی میشود. سخنرانی و میزگرد برنده ۲۰۲۵ در ماه مه برگزار شده و برای عموم بهصورت حضوری و آنلاین در دسترس خواهد بود.

استناد هیئت منصفه

جایزه معماری پریتزکر به پاس ویژگیهای استعداد، بینش و تعهد اعطا میشود که بهطور مداوم موجب ارائه مشارکتهای مهم به بشریت و محیط ساختهشده از طریق هنر معماری شدهاند.

در یک زمینه جهانی که معماری در یافتن پاسخهای مناسب به چالشهای اجتماعی و محیطی بهسرعت در حال تحول دچار مشکل است، لیو جیاکون پاسخهای متقاعدکنندهای ارائه داده است که همزمان زندگی روزمره مردم و هویتهای جمعی و معنوی آنها را گرامی میدارد.

از طریق مجموعهای برجسته از آثار با انسجام عمیق و کیفیت مداوم، لیو جیاکون جهانهای نوینی را تصور و خلق میکند که از هرگونه محدودیت زیباشناختی یا سبکی آزادند. او به جای پیروی از یک سبک مشخص، راهبردی را توسعه داده است که هرگز بر روش تکراری متکی نیست، بلکه بر ارزیابی ویژگیها و نیازهای خاص هر پروژه بهصورت متفاوت تمرکز دارد. به این معنا که لیو جیاکون واقعیتهای موجود را میگیرد و آنها را بهگونهای مدیریت میکند که گاهی یک سناریوی کاملاً نو از زندگی روزمره ارائه میدهد. فراتر از دانش و تکنیک، او عقل سلیم و خرد را به جعبهابزار طراح میافزاید.

محیط ساختهشده اغلب در جهتهای متضاد کشیده میشود. در حالی که تراکم به نظر راهحل پایدارتری برای زندگی مشترک انسانها است، کمبود فضا معمولاً به معنای کیفیت پایین زندگی است. لیو جیاکون اصول تراکم را از طریق همزیستی بازاندیشی میکند و راهحلی هوشمندانه میآفریند که نیروهای متضاد را متعادل میکند. از طریق پروژههای تحولآفرینی مانند «ویست ویلیج» در چنگدو، او الگوی فضاهای عمومی و زندگی اجتماعی را بازتعریف میکند. او روشهای نوینی برای زندگی جمعی و مستقل اختراع میکند که در آن تراکم به معنای ضد یک سیستم باز نیست. همچنین امکان سازگاری، گسترش و تکرارپذیری را فراهم میآورد. لیو جیاکون زندگیای را که ساکنان به پروژههایش میآورند، ارتقا میدهد و میپذیرد و معماریای خلق میکند که با حضور مردم فعال میشود.

در آثار لیو جیاکون، هویت هم به فرد و هم به حس جمعی تعلق به یک مکان مربوط میشود. او سنتهای چینی را بهعنوان سکویی برای نوآوری بازمیبیند، بدون اینکه دچار نوستالژی یا ابهام شود. برای او، هویت به تاریخ یک کشور، ردپاهای شهرهایش و یادگارهای جوامعش اشاره دارد. در عین حال، او ابعاد محلی و جهانی را با نتایجی بیسابقه ترکیب میکند. در موزههای ظریف و بهیادماندنیاش مانند موزه آجر کوره امپراتوری سوژو یا موزه شویجینگفانگ در چنگدو، معماری جدیدی خلق میکند که همزمان یک سند تاریخی، یک زیرساخت، یک چشمانداز و یک فضای عمومی برجسته است. در یادبود هو هویشان در چنگدو، او درمییابد که هویت مسألهای است هم از نظر حافظه جمعی و هم شخصی و با درخشش، دیدگاه فردی را به عنصری بنیادین در شکلدهی مکان تبدیل میکند تا بعد جمعی آن احیا شود.

لیو جیاکون همچنین به دنبال سطحی از فناوری است که نه زیاد پیشرفته باشد و نه ضعیف، بلکه «مناسب» بر اساس خرد محلی و همچنین مصالح و مهارتهای موجود باشد. از پروژههای ابتدایی خود، او زبان معماری رایج را شکسته تا ویژگیهای سادگی را، برگرفته از منابع در دسترس، معرفی کند. صداقت او در استفاده از مصالح اجازه میدهد که آنها خودِ آنچه هستند را بیان کنند، زیرا تمامیت آنها نیازی به واسطه یا نگهداری ندارد. این رویکرد همچنین امکان میدهد که مصالح بدون ترس از فرسودگی، در گذر زمان دوام آورند، چرا که حافظه جمعی در درون آنها نهفته است.

به این منابع فرهنگی و اجتماعی موجود، لیو جیاکون طبیعت را نیز میافزاید و مناظری نو در دل منظره ایجاد میکند. از ویست ولیج تا بازسازی منطقه غار تیانبائو در شهر ارلانگ در لوجو، و تا موزه هنر سنگی لوئییوان در چنگدو، محیطهای ساختهشده و طبیعی در یک رابطهی متقابل همزیستی دارند و همسو با کهنترین فلسفه و سنتهای چینی عمل میکنند.

به پاس پذیرفتنِ دوالیسم دیستوپیا/اتوپیا بهجای مقاومت در برابر آن و نشان دادن چگونگی میانجیگری معماری میان واقعیت و ایدهآلیسم، ارتقای راهحلهای محلی به چشماندازهای جهانی، و توسعه زبانی که جهانی عادلانه از نظر اجتماعی و محیطزیستی را توصیف میکند، لیو جیاکون بهعنوان برنده جایزه پریتزکر ۲۰۲۵ معرفی شد.

Liu Jiakun

This translation was carried out by Mohammadreza Khalili, a master’s degree student in architecture

(English)

Biography

Born in 1956 in Chengdu, People’s Republic of China, he spent much of his childhood in the corridors of Chengdu Second People’s Hospital, founded as Gospel Hospital in 1892, where his mother was an internist. He credits the environment of the Christian medical institute for cultivating his lifelong inherent religious tolerance. Although nearly all of his immediate family members were physicians, he displayed an interest for creative arts, exploring the world through drawing and literature, eventually prompting a teacher to introduce architecture as a profession.

At seventeen, Liu was part of China’s Zhiqing, or program of “educated youth” assigned to vocational peasant farming in the countryside. Life, at the time, felt inconsequential, until he was accepted to attend the Institute of Architecture and Engineering in Chongqing (renamed Chongqing University) in 1978. Admittedly, he didn’t fully comprehend what it meant to be an architect but, “like a dream, I suddenly realized my own life was important.”

Liu graduated with a Bachelor of Engineering degree in Architecture in 1982 and was amongst the first generation of alumni tasked with rebuilding China during a transformative time for the nation. Working for the state-owned Chengdu Architectural Design and Research Institute in his early career, he volunteered to temporarily relocate to Nagqu, Tibet (1984–1986), the highest region on earth, because, “my major strength of the time seemed to be my fear of nothing, and, in addition, my painting and writing skills.” During those years and the several that followed, he was an architect by day, but an author by night, deeply engrossed in literary creation.

He nearly relinquished his architecture career until attending the 1993 solo architectural exhibition of Tang Hua, a former classmate from university, at the Shanghai Art Museum, reigniting his passion for the profession and fueling a new mindset that he, too, could deviate from prescribed societal aesthetics. He considers this transformational realization—that the built environment could serve as a medium for personal expression—as the moment that his architectural career truly began. He would soon experience his most formative years of intellectual growth, debating the purpose and power of architecture with contemporaries, including artists Luo Zhongli and He Duoling, and poet Zhai Yongming.

“I always aspire to be like water—to permeate through a place without carrying a fixed form of my own and to seep into the local environment and the site itself. Over time, the water gradually solidifies, transforming into architecture, and perhaps even into the highest form of human spiritual creation. Yet, it still retains all the qualities of that place, both good and bad.”

He established Jiakun Architects in 1999 in Chengdu, firmly upholding the transcendent power of architecture while understanding that it is a product of community, spirituality, tradition and the preexisting. “Identity is as much about the individual as it is about the collective sense of belonging to a place. Liu Jiakun revisits the Chinese tradition without nostalgic approach nor ambiguity, but as a springboard for innovation,” states the 2025 Jury Citation, in part. “[H]e creates new architecture that is at once a historical record, a piece of infrastructure, a landscape and a remarkable public space.”

Spanning four decades, Liu, along with his team, has built more than thirty projects, ranging from academic and cultural institutions to civic spaces, commercial buildings and urban planning throughout China, and was selected to design the inaugural Serpentine Pavilion Beijing (2018).

“Writing novels and practicing architecture are distinct forms of art, and I didn’t deliberately seek to combine the two. However, perhaps due to my dual background, there is an inherent connection between them in my work—such as the narrative quality and pursuit of poetry in my designs.”

His written works have included The Conception of Brightmoon (Times Literature and Art Publishing House, 2014), exploring the conflict between utopias and human life, Narrative Discourse and Low-Tech Strategy (China Architecture & Building Press, 1997), Now and Here (China Architecture & Building Press, 2002) and I Built in West China? (Today Editorial Department, 2009).

Liu has been featured in international exhibitions including Experimental Architecture by Young Chinese Architects – The 20th UIA World Congress of Architects (1999, Beijing, China); TU MU Young Architecture From China (2001, Berlin, Germany); Urban Creation, Shanghai Biennale (2002, Shanghai, China); the 1st, 3rd and 7th Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism/Architecture (2005, 2009 and 2017, Shenzhen, China); the 11th and 15th International Architecture Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia (2008 and 2016, Venice, Italy); the 56th International Art Exhibition of La Biennale di Venezia (2015, Venice, Italy); Now and Here – Chengdu | Liu Jiakun: Selected Works (2017, Berlin, Germany); and Super Fusion – Chengdu Biennale (2021, Chengdu, China).

Currently, he is a visiting professor at the School of Architecture Central Academy of Fine Arts (Beijing, China), and has previously lectured at Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine (Paris, France), Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, Massachusetts, United States of America), Royal Academy of Arts (London, United Kingdom), and leading institutions in China. Awards have included the Far Eastern Architectural Design, Outstanding Award (2007 and 2017); ASC Grand Architectural Creation Award (2009); Architectural Record China Awards (2010); WA Awards for Chinese Architecture (2016); Building with Nature, Architecture China Award (2020); Sanlian Lifeweek City for Humanity Awards for Public Contribution (2020); and UNESCO Asia-Pacific Awards for Cultural Heritage Conservation, New Design in the Heritage Contexts (2021).

Liu continues to practice and reside in Chengdu, China, prioritizing the everyday lives of fellow citizens through his works.

annou(Liu Jiakun's theoretical foundations)

Chicago, IL (March 4, 2025) – The Pritzker Architecture Prize announces Liu Jiakun, of Chengdu, People’s Republic of China, as the 2025 Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the award that is regarded internationally as architecture’s highest honor.

“Architecture should reveal something—it should abstract, distill and make visible the inherent qualities of local people. It has the power to shape human behavior and create atmospheres, offering a sense of serenity and poetry, evoking compassion and mercy, and cultivating a sense of shared community,” expresses Liu.

Intertwining seeming antipodes such as utopia versus everyday existence, history versus modernity, and collectivism versus individuality, Liu offers affirming architecture that celebrates the lives of ordinary citizens. He upholds the transcendent power of the built environment through the harmonizing of cultural, historical, emotional and social dimensions, using architecture to forge community, inspire compassion and elevate the human spirit.

“Through an outstanding body of work of deep coherence and constant quality, Liu Jiakun imagines and constructs new worlds, free from any aesthetic or stylistic constraint. Instead of a style, he has developed a strategy that never relies on a recurring method but rather on evaluating the specific characteristics and requirements of each project differently. That is to say, Liu Jiakun takes present realities and handles them to the point of offering sometimes a whole new scenario of daily life. Beyond knowledge and techniques, common sense and wisdom are the most powerful tools he adds to the designer’s toolbox,” states the 2025 Jury Citation, in part.

Liu creates public areas in populated cities where the luxury of space is largely absent, forging a positive relationship between density and open space. By multiplying typologies within one project, he innovates the role of civic spaces to support the breadth of requisites for a diverse society. West Village (Chengdu, China, 2015) is a five-story project that spans an entire block, visually and contextually contrasting with the matrix of characteristically mid- and high-rise buildings. An open yet enclosed perimeter of sloping pathways for cyclists and pedestrians envelopes its own vibrant city of cultural, athletic, recreational, office and business activities within, while allowing the public to view through to the surrounding natural and built environments. Sichuan Fine Arts Institute Department of Sculpture (Chongqing, China, 2004) displays an alternate solution to maximizing space, with upper levels protruding outward to extend the square footage of a narrow footprint.

“Cities tend to segregate functions, but Liu Jiakun takes the opposite approach and sustains a delicate balance to integrate all dimensions of the urban life,” comments Alejandro Aravena, Chair of the Jury and 2016 Pritzker Prize Laureate. He continues, “In a world that tends to create endless dull peripheries, he has found a way to build places that are a building, infrastructure, landscape and public space at the same time. His work may offer impactful clues on how to confront the challenges of urbanization, in an era of rapidly growing cities.”

Throughout his works, Liu demonstrates a reverence for culture, history and nature, chronicling time and comforting users with familiarity through modern interpretations of classic Chinese architecture. Flat eaves of the Suzhou Museum of Imperial Kiln Brick (Suzhou, China, 2016) and window walls of Lancui Pavilion of Egret Gulf Wetland (Chengdu, China 2013) reimagine the form of pavilions dating back many millennia. Tiered balconies of Novartis (Shanghai) Block – C6 (Shanghai, China, 2014) are reminiscent of towers representing many dynasties. Luyeyuan Stone Sculpture Art Museum (Chengdu, China, 2002), housing Buddhist sculptures and relics, is modeled after a traditional Chinese garden, balancing water and ancient stones to reflect the natural landscape. Believing that the human relationship with nature is reciprocal, buildings both emerge and dissolve within their surroundings, such as The Renovation of Tianbao Cave District of Erlang Town (Luzhou, China, 2021) nestled in the lush cliffside landscape of Tianbao Mountain. Local and wild flora is featured in all of his works, as bricks are paved upended to enable grasses to flourish through the core holes, indigenous bamboo groves are planted in new sites, and floors and ceilings are designed with openings to allow the continuance of existing trees.

His honest architecture presents the sincerity of textural materials and processes, displaying imperfections that endure, rather than degrade, through time. He disfavors manufactured product, preferring traditional craft and often using raw local materials that sustain the economy and environment, built for and by the community. The Department of Sculpture building exposes swirling details of authentic Chongqing sand plastering handiwork that are left visible rather than honed. He revives materials—and spirits—upcycling rubble from the ruins of the 2008 Wenchuan earthquake and strengthening it with local wheat fiber and cement to produce fortified bricks with greater physical and economic efficiency than the original. The “Rebirth Bricks” can be found extensively throughout the Novartis building, Shuijingfang Museum (Chengdu, China, 2013) and West Village, his largest work. The devastation also yielded his smallest work to date, Hu Huishan Memorial (Chengdu, China, 2009), in the form of a permanent cement relief tent, exhibited not only for a 15-year-old girl in the aftermath of destruction, but for the collective memory of an entire nation in mourning.

“Liu Jiakun uplifts through the process and purpose of architecture, fostering emotional connections that unite communities,” remarks Tom Pritzker, Chairman of The Hyatt Foundation, which sponsors the award. “There is a wisdom in his architecture, philosophically looking beyond the surface to reveal that history, materials and nature are symbiotic.”

Liu’s career spans over four decades, with more than thirty projects ranging from academic and cultural institutions to civic spaces, commercial buildings and urban planning throughout China. Significant works also include Museum of Clocks, Jianchuan Museum Cluster (Chengdu, China, 2007); Design Department on new campus, Sichuan Fine Arts Institute (Chongqing, China 2006), Lodging Center of China International Practice Exhibition of Architecture (Nanjing, China, 2012), Chengdu High-Tech Zone Tianfu Software Park Communication Center (Chengdu, China, 2010), and Songyang Culture Neighborhood (Lishui, China, 2020).

Liu is the 54th Laureate of the Pritzker Architecture Prize and the founder of Jiakun Architecture, established in 1999. Born in Chengdu, China, he resides and works in his native city. He will be honored at a celebration in Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates this spring, and globally with a virtual ceremony video this fall. The 2025 Laureate Lecture and Panel Discussion will be held in May and open to the public in-person and online.

Jury Citation

The Pritzker Architecture Prize is conferred in acknowledgment of those qualities of talent, vision, and commitment, which have persistently produced significant contributions to humanity and the built environment through the art of architecture.

In a global context where architecture is struggling to find adequate responses to fast evolving social and environmental challenges, Liu Jiakun has provided convincing answers that also celebrate the everyday lives of people as well as their communal and spiritual identities.

Through an outstanding body of work of deep coherence and constant quality, Liu Jiakun imagines and constructs new worlds, free from any aesthetic or stylistic constraint. Instead of a style, he has developed a strategy that never relies on a recurring method but rather on evaluating the specific characteristics and requirements of each project differently. That is to say, Liu Jiakun takes present realities and handles them to the point of offering a whole new scenario of daily life. Beyond knowledge and technique, he adds common sense and wisdom to the designer’s toolbox.

The built environment is often being pulled in opposite directions. While density appears to be a more sustainable solution for people to live together, the scarcity of space usually implies a poor quality of life. Liu Jiakun rethinks the fundamentals of density through cohabitation, crafting an intelligent solution that balances the opposite forces at play. Through transformative projects like the West Village in Chengdu, he reshapes the paradigm of public spaces and of community life. He invents new independent, shared ways of living together in which density does not represent the opposite of an open system. He also enables adaptation, expansion and replicability. Liu Jiakun enhances and welcomes the life that inhabitants bring to his projects, creating an architecture activated by its publics.

In Liu Jiakun’s work, identity is as much about the individual as it is about the collective sense of belonging to a place. He revisits the Chinese tradition as a springboard for innovation devoid of nostalgia or ambiguity. For him, identity refers to a country’s history, the traces of its cities and the relics of its communities. At the same time, he integrates the local and global dimensions with unprecedented results. In his subtle, memorable museums, Suzhou Museum of Imperial Kiln Brick or the Shuijingfang Museum in Chengdu, he creates new architecture that is at once a historical record, a piece of infrastructure, a landscape, and a remarkable public space. In the Hu Huishan Memorial in Chengdu, he understands that identity is a matter of both collective and personal memory, brilliantly elevating the individual perspective to a foundational element of place-making in order to revive a communal dimension.

Liu Jiakun also seeks a level of technology that is neither high nor low but rather the “appropriate” one based on local wisdom as well as materials and craftsmanship available. Since his early projects, he has broken the current architectural language to introduce the qualities of simplicity, deriving from the resources at disposal. His sincerity in the use of materials lets them speak for what they are, as their integrity does not require mediation or maintenance. It also enables them to age without fear of deterioration because the collective memory is held within them. To such available cultural and social resources, Liu Jiakun adds nature creating new landscapes within the landscape. From the West Village to the Renovation of Tianbao Cave District of Erlang Town in Luzhou, to the Luyeyuan Stone Sculpture Art Museum in Chengdu, the built and natural environments co-exist in a reciprocal relation and in line with the most ancient Chinese philosophy and tradition. For embracing rather than resisting the dystopia/utopia dualism and showing us how architecture can mediate between reality and idealism, for elevating local solutions into universal visions, and for developing a language that describes a socially and environmentally just world, Liu Jiakun is named the 2025 Pritzker Prize Laureate.

Ceremony Louvre abu Dhabi

Created by an exceptional agreement between the governments of Abu Dhabi and France, Louvre Abu Dhabi was designed by Jean Nouvel, 2008 Pritzker Architecture Prize Laureate, and his team, Ateliers Jean Nouvel. Opened on Saadiyat Island in November 2017, the museum is inspired by traditional Islamic architecture and its monumental dome creates a rain of light and a unique social space that brings people together. Louvre Abu Dhabi celebrates the universal creativity of mankind and invites audiences to see humanity in a new light. Through its innovative curatorial approach, the museum focuses on building understanding across cultures: through stories of human creativity that transcend civilizations, geographies, and times.

The museum’s growing collection is unparalleled in the region and spans thousands of years of human history, including prehistoric tools, artifacts, religious texts, iconic paintings, and contemporary artworks. The permanent collection is supplemented by rotating loans from 19 French partner institutions, regional and international museums.

sources

This translation was carried out by Mohammadreza Khalili

a master’s degree student in architecture